We’re sitting at the top of a sloping High Eden vineyard. There’s a cool breeze that strikes a stark contrast to the heat of the valley floor and, after travelling through the patchy paddocks of Tanunda, the landscape here is surprisingly lush. We’re at Wroxton Grange, which is known for its old-vine riesling. The Barossa Valley is famed for its intense red wines, but take a turn up to the Eden Valley and you’ll find the source of elegant whites.

Now and then

“You’re not a Barossan until you have three in the ground” is a phrase I become familiar with over the next few days. The Barossa upholds its traditions and there’s a pride in the place that quickly becomes clear.

A community of Silesian migrants settled in South Australia in 1836, among them many farmers. They found the Mediterranean climate in the Barossa suitable for growing fruit – especially grapes – and soon names such as Yalumba, Henschke and Saltram were up and running in what is heavily ancestral territory.

Today, this is a region in hot demand, but that hasn’t always been the case. Talk to Peter Lehmann’s Malcolm Stopp and he remembers a time, in the 1980s, when the Barossa was using shiraz fruit for muffins – hard to imagine the variety needing to be rethought as a tea-time treat.

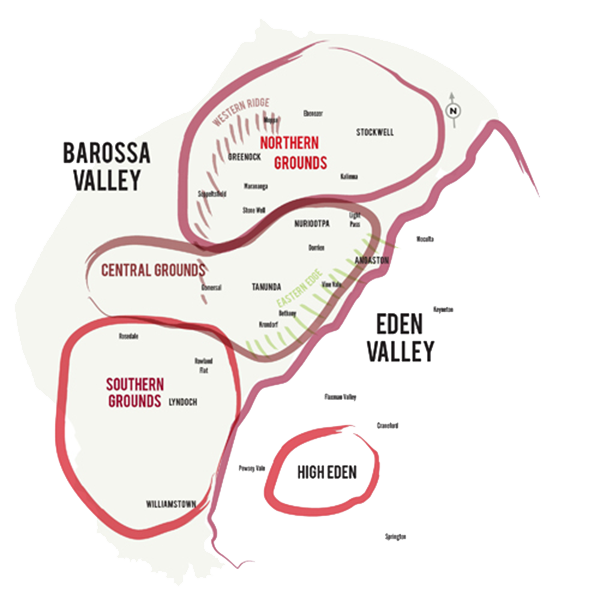

Sub-regionality and seven soils

Back in the Eden Valley, we’re 400-odd metres above sea level. Across the road from us is Grant Burge and around the bend is Yalumba’s Heggies. At the peak is Mount Pleasant and Moculta is at the entrance. Lyndoch is the lowest part of the Barossa, while St Kitts is right up the top. There are more than 20 defined sub-regions here. All of these slopes and contours are a dream for winemaking, offering plenty of personality in the fruit and its resulting wines.

Schist, clay, ironstone, limestone, loam, gravel and sand are some of the elements underfoot. Vine Vale represents the deep-sand sites of the region, while Western Ridge areas Greenock and Marananga showcase hotter, rockier soils. Northern sub-regions Moppa and Ebenezer are popular among winemakers because of the rich, red clay.

The individuality of the various sites offers an opportunity for a European style of sub-regional labelling. Wolf Blass is capitalising on this with its Estates of the Barossa bottles, and Alex Head is another who is featuring this across his Head Wines range. The opposite, however, is also true, with a wide net of wineries able to label bottles simply ‘Barossa’: whether from the cool of High Eden or the warm of the valley floor.

More than shiraz

The Barossa and shiraz are best mates, but it has other friends. Look closely and you’ll find everything from Mediterranean wines suited to the environment to extra-experimental, boundary-pushing styles.

First stop is Peter Lehmann’s Tanunda cellar door. While the winery was only established in the late 1970s, it’s strongly steeped in the traditions of the region. The son of a preacher man and a fifth-generation Barossan, Peter got his start with Yalumba in 1946.

Peter Lehmann is now under the umbrella of Casella Family Brands, but its core values remain; its essence lies in the grower-winery relationship. From Yalumba, Peter went on to work at Saltram and it was here that his role as a grower advocate was established. As Saltram’s cellar manager he was asked to deliver the news to more than 180 growers that their fruit, a large part of their livelihood, wasn’t required. He refused and instead rallied fellow winemakers to take on responsibility for it – harvesting it, vinifying it and selling it for enough profit to pay them. Soon after, Peter, Leonie Lange (one of Australia’s first female winemakers), Andrew Wigan and Charles Melton started their own outfit, bringing with them many of the growers they had supported at Saltram.

Peter passed away in 2013, but today his legacy lives on. The brand has 140 growers across the valley and that’s for the freedom to choose the best parcels each year as well as a desire to support as many in the region as possible. Nigel Westblade took over from Ian Hongell as chief winemaker in 2017, when Ian moved on to Torbreck Wines, joining a team that includes Tim Dolan (ex Saltram) and Peter Scholz (also with his own winery, The Willows).

We’re the first to see the 2012 Peter Lehmann Margaret Semillon and Wigan Riesling – wines that aren’t released until they’re at least five years old. Fruit for The Margaret Semillon is sourced from lower parts of the valley, while grapes for The Wigan come from High Eden growers.

The Stonewell is Peter Lehmann’s flagship shiraz and while in some years it’s made with fruit from the Stonewell Vineyard, it’s not always. Besides a gradual reduction of oak in the wine, its original style has been maintained over time. The Mentor is a point of difference: a cabernet-dominant blend showcasing parcels from the coveted north-west section of the Barossa.

Moving from Tanunda to the Western Ridge, we arrive at Craig Isbel’s Izway Wines. Izway is a passion project for Craig; from 2002 until recently, his day job was at Torbreck. “It was a remarkable place to be educated in the world of Barossa wine and a lot of the philosophies from there have been carried over to Izway,” he says.

Today is what Craig calls a ‘fruit day’. Steel fermenters are full with plush, purple fruit and the guys are in their gumboots ready to punch-down the grapes. Among the ferment bins are Ebenezer shiraz planted 1950, Moppa shiraz planted 1895 and home-block (Greenock) grenache propagated from vines planted 1901. Craig is all for Barossa grenache and in this part of the valley, it’s what he believes works best.

Seppeltsfield’s bush vines stretch out into the distance across the road and Craig’s own lie behind the winery. “Part of the reason I bought this property was because of the location, and the other part was that there was a small vineyard I didn’t think I could kill, he says. Next door to the winery is the tasting room he built. Craig shares that its proximity to the winemaking process was an intentional part of the design. Wear the right footwear and you might even get to stomp some grapes. “Wine is as much about the experience and having some fun as anything else,” he says.

Izway has eight wines, all reds. Half of those are non-traditional varietals. The rest represent the powerful, structured wines we’ve come to expect from the Barossa. My favourite quirk of the line-up is the wine names. The Three Brians is a grenache named for Craig’s business partner Brian Conway, his father Brian and Conway’s father Brian. Angelo is an anglianico from fruit grown onsite named after an Italian who worked at the winery. But the greatest is perhaps the Harold – an Eden Valley shiraz named after a fishing rod.

Our final stop is the pared-back winery/shed of visionary winemaker Tom Shobbrook. He makes wines that are freaky and fun – not for everyone, but the Barossa needs blokes like Tom to challenge the status quo. His wines are also successful, having captured the imaginations of sommeliers across the country and further afield.

There are 21 acres here, mostly shiraz with small crops of merlot and cinsault. Since returning from Italy, where Tom ran a farm with vineyards and olive groves, he’s overhauled the approach and it’s now all organic.

The most classic wine he shows us is a merlot he makes for his mum. It’s stunning – you don’t see many single-varietal expressions like it. “Mum planted merlot when I was in Italy,” he says. “She wanted to plant cabernet and I convinced her not to, but I forgot she was going to plant something, so that was it. I didn’t want anything to do with merlot here, but in 2008 we made that wine and I loved it. I love what merlot does on red soil.”

Others we try include a rosé called Poolside – a slurpable, guava-pink wine that could easily be matched with many different dishes. There’s a petillant-naturel take on the rosé called Making Space and a medium-bodied, whole-bunch shiraz. The texture and acidity of Tom’s creations make them gustatory wines – they’re lower in alcohol and get the mouth watering, so it’s little wonder they’re cropping up on wine lists everywhere.

Tom is interested in what he calls “lost Barossa varieties”. He has a wine called Sammion made from old-vine semillon, and an aromatic white blend called Giallo (‘yellow’ in Italian) that’s a mix of muscat, riesling and semillon. He makes a few hundred bottles of cinsault and a bit of unfortified sherry. The most out-there drink we try is a ‘cider’, 60 per cent pear and 40 per cent mourvedre, the colour of red wine.

The Barons

On our final night, we attend the Barons of the Barossa event at Chateau Tanunda – a who’s-who of wine in the region. Before the ceremony we hobnob with Helen and Grant Burge, the Henschke family and Pewsey Vale’s Louisa Rose. Maggie Beer emcees the evening and one of the senior barons collects new barons by banging his sceptre (yes, sceptre) next to their chair. The new recruits walk up to the stage to accept a robe and drink from a goblet filled with fortified wine, sealing the deal with the salute, “Glory to the Barossa”.

Bizarre? Perhaps. But I can’t think of a better representation of the region. It has hubris and a solid sense of self. Plus, its roll call of winemakers and viticulturists is illustrious enough to warrant such a fraternity.

Glory to the Barossa, indeed.

Find everything you need to know about the Barossa in our essential guide.