Meet the big Australian. Shiraz, that is.

Considered by many to be the most important wine grape in the country, it occupies 30 per cent of the national vineyard, and supplied close to a quarter of the total crush of all wine grapes in the 2018 vintage.

These statistics tell of its economic power domestically. Retailers still marvel at its continued popularity, while exporters celebrate its stature as a global ambassador.

Shiraz grows successfully north, south, east and west: yes, Queensland to Tasmania, New South Wales to Western Australia, South Australia to Victoria, on mountain slopes and along the great rivers, in sand, clay and volcanic ground. It’s the workhorse and the megastar.

Not surprisingly, given all those factors, shiraz is not the simple red monolith many imagine. Over the past two decades, and especially in the past five years, it’s been recognised that shiraz can be a many splendoured thing and is able to deliver unlimited expressions from every corner of our winemaking landscape.

Shiraz can be a many splendoured thing and is able to deliver unlimited expressions from every corner of our winemaking landscape.

It was the frontline soldier during the years when extreme ripeness, vanilla-cream American oak and raw alcoholic power were, in hindsight, unlikely fashion statements. It has been a messenger for defining regionality. In its keystone regions of South Australia’s Barossa and McLaren Vale, it has been the tool to unlock the secrets of subdistrict, village and single-site diversity.

And now it is all that and much, much more. Authenticity, individuality, personality and drinkability are the drivers of winemaking today. “Everyone is trying to make wines that have their own look about them, from the vineyard, in the winery and in their regions,” says Yalumba chief winemaker Louisa Rose. “And drinkability is a major factor in how we approach our winemaking.”

Yalumba’s own market research has shown that in the $15 to $30 price range, consumers are seeking wines that are more medium-bodied than ever; younger, more youthful, fresher, softer and more food-friendly – wines that are ready to drink now rather than for cellaring.

The way that influences her team’s winemaking, seen clearly in Yalumba’s new Samuel’s Collection range, has resulted in less extraction of fruit, less time on skins, cooler fermentation, less oak and less new oak, as well as larger maturation vessels, so it is now a support flavour to the wine rather than a dominant one.

Similar stories repeat in almost every region. The overarching desire to “tone things down”, according to Halliday 2018 Winemaker of the Year Paul Hotker, of Bleasdale in Langhorne Creek, has led to more vibrant shiraz wines that come from an increased understanding of what makes the variety inherently delicious. “We’re all trying to make better wine and we have better technical ability now as an industry to achieve that,” Paul says.

The increase in understanding vineyards and the winery floor has also led to a wider change in philosophy and process, often generational, towards creating new, gentler expressions of shiraz that have perhaps taken a lead from the way pinot noir and grenache have thrilled winemakers and drinkers alike in recent years.

An evolution in shiraz is certainly here, according to renowned Barossa winemaker John Duval and son Tim. “There’s a proliferation of younger winemakers in the Barossa with experimental approaches to shiraz that are breathing life into the whole district,” John says.

Tim agrees it’s been a good thing. “It’s resulted in shiraz that is not simply painted with the same brush,” he says. “Now, along with traditional practices, there’s earlier picking, more whole bunch being used, some carbonic maceration, and what have become the cliches of moving away from American oak to French and respecting your site, all resulting in a great divergence of style.”

Tim and John Duval aim to create modern shiraz styles that capture the essence of the Barossa.

Tim and John Duval aim to create modern shiraz styles that capture the essence of the Barossa.The Duvals source fruit from the Barossa Valley floor and higher, cooler Eden Valley, which offer totally different expressions of shiraz. Their aim is to most importantly capture the variety’s obvious characters, a recognisable regional style of richness and generosity, while gradually refining their winemaking to encourage greater elegance and drinkability. “You can have something that’s very Barossan with a modern attitude,” Tim says.

Both in the Barossa and McLaren Vale, long-term geology mapping projects have resulted in wine growers and makers looking more intently at their own vineyards, and what they genuinely create in their fruit characteristics.

McLaren Vale’s complex geology map has had a major influence in the region, says Chapel Hill winemaker Michael Fragos. “It really makes us as a region think more about where the vines are grown, and once you consider that, it’s inevitable that we all want our wines to showcase those site characters,” he says.

Given there are hundreds of separate vineyard sites in the district, and 57 per cent of the region’s grapes are shiraz, that may suggest a fracturing of style within the region. However, Michael argues that McLaren Vale has realised the strength of its shiraz is its familiar generosity and roundness, no matter recent trends and fashions.

“It’s our sunshine, our soils and our terroir that suit that style of shiraz, though there was definitely a need for some correction,” Michael says. “From a district perspective, the wines are definitely purer than they were 15 to 20 years ago. There’s more balance, and when I show [my wines] around the world now, there’s more interest in the newer styles.”

A move to more single-site expressions is considered one reason for a revitalised interest in the variety. This relates to regions with a well-established history in their approach, such as the Hunter Valley, as well as districts that sit somewhat under the shiraz radar, including Clare Valley and Heathcote. All have individual climatic and soil-driven elements that influence regional stylings.

In the Hunter, the focus tends to be on the vineyard and block, according to Mount Pleasant winemaker Adrian Sparks, with harvest-time weather patterns having a major impact on the regional characteristics. “We tend to grow our wines to get them off early, so we don’t get the weight or the ripeness other places do,” Adrian says. “We retain a lot of acidity and produce medium-bodied styles, which have good drinkability as well as great chemistry for ageing, and are intense and savoury. This is what the Hunter Valley does – beautiful drinking wines – and I reckon people are getting it and the market is following us.”

Clare Valley shiraz covers a wide spectrum of styles, according to Kerri Thompson of Wines by KT.

Clare Valley shiraz covers a wide spectrum of styles, according to Kerri Thompson of Wines by KT.

In Clare, Kerri Thompson from Wines by KT recognises the evolution in her region’s shiraz has also been driven by single-site styles and the microclimates they represent. Winemakers are looking for more primary fruit in finer frames and seeking inspiration from iconic blends with other varietals – mataro and malbec included – made famous by Wendouree. “The wines here do range from the more funky, bunchy styles to the more oaky sort of thing,” Kerri says. “There are always people looking for those massive styles, but I see a lot of people through cellar door enjoying the opportunity to revisit shiraz in a finer version. The take-home message in Clare is that shiraz comes in all shapes and sizes – and that’s incredibly exciting.”

By default, if you stick shiraz in any of the 65-odd regions around Australia – and it does grow in most of them – you get different expressions of the variety, says Shaw + Smith co-proprietor Michael Hill Smith.

“Shiraz has moved on from being a story all about power, weight and older-fashioned winemaking to now offer a fascinating insight into regional diversity,” Michael says. Both he and his cousin and business partner Martin Shaw have long been advocates of cooler-climate shiraz, excited by the “historically serious” wines from Best’s Great Western as well as the “profound” impact of Clonakilla’s shiraz from the Canberra District.

In their own Adelaide Hills territory, they are no longer hung up on the weight of their shiraz in the glass and seek higher acidity, fresher fruit and more aromatics, presenting a “perfect counter” to what is perceived as traditional Australian shiraz.

When Michael judged his first wine show in 1980, he recalls, the word “brightness” was never used when talking about red wine. “We talked about power, and weight and intensity – never brightness or liveliness, freshness or energy,” he says. “All those words relate to shiraz today – and that’s why modern Australian shiraz, wherever it comes from, is more interesting than ever, and seems to have found a new energy both in wine style and in the marketplace.”

This article first appeared in Halliday magazine. Become a member and enjoy digital access to the publication.

Latest Articles

-

![Default article tile image]()

News

Does the Adelaide Hills have an image problem?

1 day ago -

![Default article tile image]()

From the tasting team

Sustainable and beyond: Marcus Ellis on sustainability in the wine industry

1 day ago -

![Default article tile image]()

News

The reinvention of the Aussie sommelier

1 day ago -

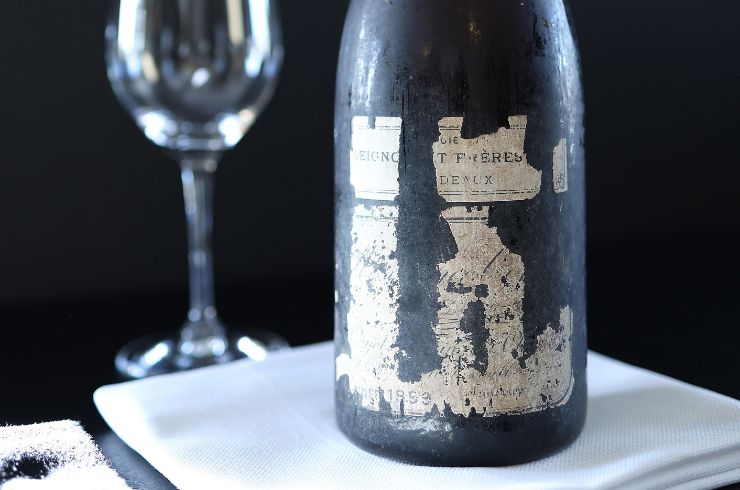

News

Why a co-owner of Bass Phillip decided to taste, instead of trade, this 127-year-old bottle of wine

2 days ago